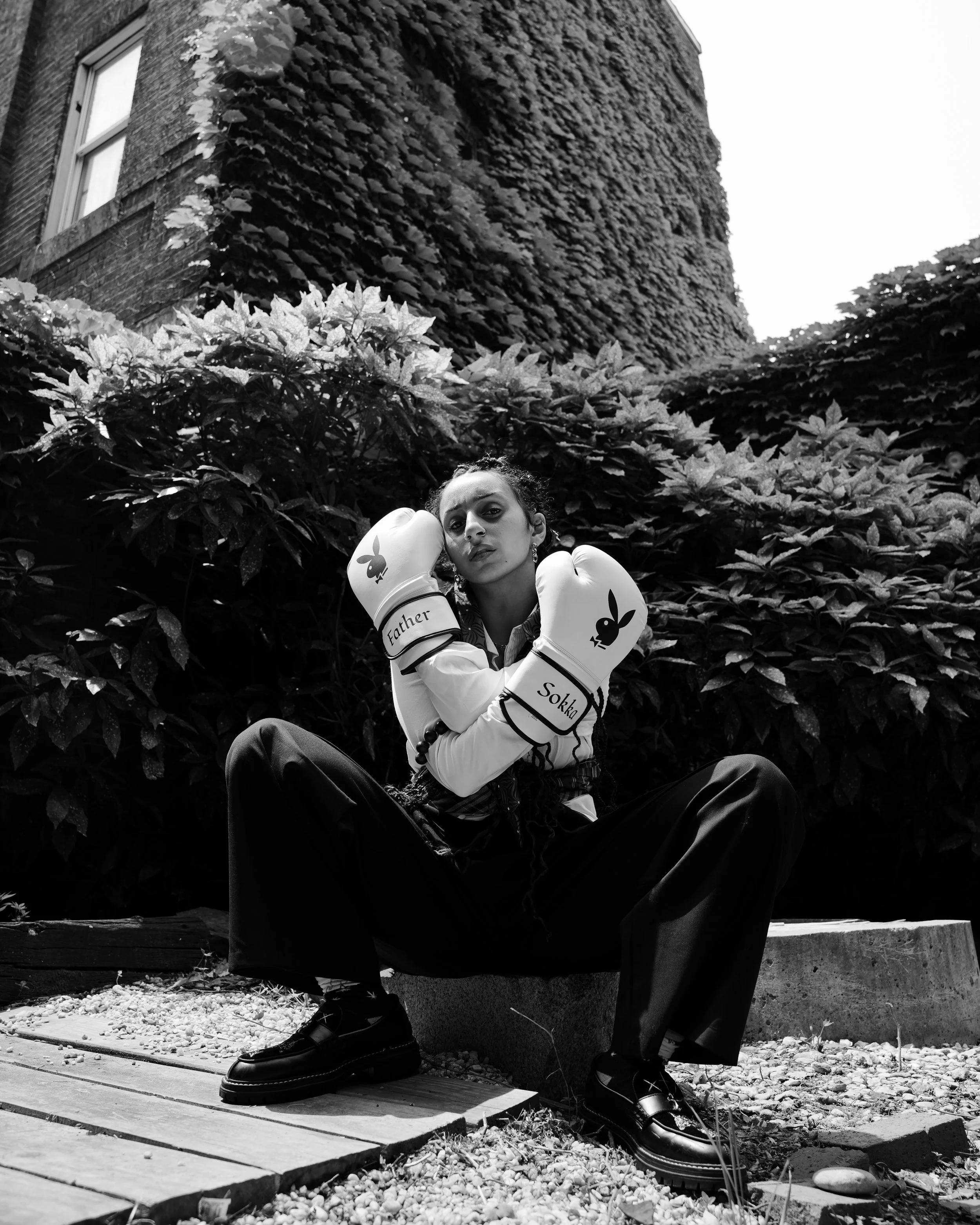

Father Sokka Pulls No Punches

photo by BRANDON BATTLE, fashion by BRIA JONESwith RON DAVID STUDIO, SAIMAR, CARPOSKA

The name came first as a joke – a high school nickname borrowed from Avatar and crowned with "Father" by internet fate. But the artist behind it is dead serious. Father Sokka, the non-binary Ethiopian-Eritrean rapper stitching together a D.C. upbringing, Baltimore’s grit, and a diaspora’s defiance, makes music that hits like a right hook: calculated, cathartic, and impossible to ignore. Fresh off a housewarming for their new residence in Baltimore, we talked to Sokka about their return to music, plenty of personal lore, and their read on the DMV’s underground rap scene.

Their origin story reads like testimony: a breakup sparked their return to the mic; a spontaneous freestyle garnered acclaim; and a lifetime of quiet battles with anxiety and economic hardship now fuels bars that oscillate between sharp technicality and raw vulnerability. Recording entirely at home in a pay-to-play industry, they value accessibility and spit truths that reveal their character: "I sound like someone who doesn’t care—but I do." Recently graduating from college, Father Sokka is drafting the next chapter: THEM, an EP with doses of Ethiopian heritage – sampling Mulatu Astatke, the godfather of Ethiopian jazz, for one track – and hardbody bars that bring you into their world. Out the Wrapper was just the warm-up. The main event starts now. Here is my convo with Father Sokka:

Damon Barnes: How did you come up with the name Father Sokka? What's the lore behind it?

Father Sokka: The lore is super duper duper duper simple. Somewhere between freshman and sophomore years of high school, I shaved the sides of my head and a friend of mine said I looked like Sokka from Avatar. And then essentially all the dudes in my neighborhood, I was transferring over to the neighborhood high school. Um, they just couldn't really say my government name. It was very foreign.

So it was just easier for folks to call me Sokka. And then I transferred to my neighborhood school, and everybody called me Sokka. But the Father part was just – I don't know, like making jokes like the Daquan era of memes, and like being someone who grew up without a father, like I just kind of would joke, I'd be like, I'm the father, I'm the dad. So I made my Instagram @fathersokka, and I just had no other way to brand myself. So I just stuck to it and it really really stuck.

DB: Did you know it was going to be your artist name?

FS: No, I really didn't. I did this when I was 14, you know, so I was just playing around.

DB: Feel that. What made you return to music after going on a hiatus?

FS: I always use music as an outlet. I think I started I started publicly releasing music cuz I was upset about a horrible breakup when I was 15. So like music has always been kind of where I channel my inner hatred for the shitty things that people can do in this life. And I took a break and kind of wanted to work on just handling those things on my own. But I think I fell kind of far. I kind of just moved to one end of the spectrum of being very like hardened and not letting myself be upset for so many years. I realized that I had a lot of feelings that I needed to work through. I didn't plan to release a lot of the music.

The first song I did coming back was “Crunk” on Por Vida's Psalms For the Restless & Tired album. It was just me playing around rapping, and he ended up putting it on his like artist tape. From there, Floaters peeped my stuff. I did a Floaters freestyle. Like, this was in no way planned. Por Vida dropped that song for me, and then Floaters filmed that freestyle, and then like next thing I know like it had 40,000 views.

So then, in the midst of feeling a lot of things, I wrote a diss track called “D Rose,” and that was my first real song coming back. It was a very hateful song – it's a diss track. Like, I wanted to get a lot of feelings out. I got really sick the year approaching summer 2024. So that whole last six to eight months, I was pretty sick.

I was really struggling with a panic disorder and an eating disorder, and I was holding all of my pain inside. A lot of the experiences aggravated those ailments, and I really had to let them out. I truly feel like if I didn't let my feelings out, I would have died. And it's kind of ironic because that quote is so like iconic, but then you listen to Out the Wrapper and it's literally me being like, "Pussy, pussy, pussy, pussy, pussy. Yeah, what? Ain't nothing,” [laughs]. It was kind of step one. Like you know, your first five therapy sessions. You don't get to the root of the problem. Sometimes you just bullshit. And I think that's kind of what Out the Wrapper was for me, was just practicing using my instrument again and just talking about whatever and not really getting too much into the rawest parts of my experience – which I hope to do moving forward.

DB: I resonate with the way you were able to use art as a sort of therapeutic process. I know you've been open about dropping out of high school to support your family. You just shared some other experiences from your past. How did those experiences shape your outlook on life and art?

FS: I look at my mom - she's such a strong woman, and I hate the strong Black woman trope. But I've never really felt strong. I've always been on the more sensitive side. As much as people might see me as aggressive or strong in nature, I truly am a very sensitive person. I've gained a lot of grit and tenacity and discipline in my suffering.

On my upcoming project, I'm opening up and letting the ego down and letting the pride down and being honest. There's a huge disconnect between who I am in real life and my music. In some ways it represents some parts of me - the more lustful parts, the vices, the pimp player suave ways.

My upcoming music is definitely grittier and more honest. It's also more structured. With Out the Wrapper, I was doing anything - my producer told me I'd give him odd counts like 27 instead of 16 or 32. It made weird music. I'm learning to unpack my life experiences and finally share my story. I have much to say but aren't as vulnerable as I used to be. I'm working on that.

DB: You maintain an unfiltered expression, but there's still a journey to deepen that vulnerability with the world. I'm excited to see your progression. That leads to my next question - for people discovering you through this interview, how would you describe what they should expect?

FS: They'll find someone who doesn't give a fuck but clearly gives so many fucks. Anyone who loves music listens to mine and gets surprised. We're in an era where everyone's a rapper, and the business has become accessible yet inaccessible. We’ve created mini monopolies on the music scene. I do feel like that’s why the DMV scene struggles, because everything costs money - $50 beats, $100 studio sessions. Meanwhile, I record everything at my desk; never been to a studio. Yeah, never been to a studio. Men are creepy. Studios feel unsafe - I'd probably slap someone. Music is my home.

I wrote my first raps in fourth grade. Listeners will notice the technicality - whether they grew up on Boom Bap, Tribe Called Quest, Young Money or even the new shit, they'll hear I truly love and study this craft. To the deaf ear... fuck, I don't want to sound ableist.

When you listen to my lyrics, you'll hear someone who knows exactly what they want to say. People DM me like, “You really talk about yourself”. Like you’re not talking about some fantasy like many rappers create with their "I'm fucking bitches" personas. But, a lot of it is about picking yourself up, creating the world you want to live in, whatever fantasy, whatever vices you want, and teaching people about your actual experiences. People recognize the truth in what I say - why else would a girl expose themselves like this? I'm not chasing clout. Look at how I market - I'm just releasing music to get this shit off my chest.

Damon Barnes: You clearly have so much to say from your varied life experiences. What's some lesser-known lore about you? I didn't even know you boxed.

FS: I do like boxing. I took up boxing during my hiatus to process emotions, similar to rapping. I had spent years making myself small - staying home, off social media - until I had to relearn how to exist publicly again. Boxing and rapping helped. I can give you some lore - I love cooking. I taught myself Italian in the last couple years. Oh, and my dad came back. That shit was crazy. It's not like a normal dad coming back thing though.

But my mom left my dad and I didn't know him, didn't know his name, didn't know anything. He contacted me on Facebook during my hiatus and told me a lot about where I came from. My father's from Pakistan. Everyone knows me as a Habesha legend. No one knows I'm secretly Desi. That's some crazy lore for you. I grew up thinking I wasn't. I didn't know I was Desi growing up. I found out from a Facebook call from my dad in late 2022. Some dude with pretty much my last name called me on Facebook.

I happened to have been teaching myself Italian the year before, not taking it super seriously. My mom didn't want to practice with me. My brother lives in a different time zone, we don't really practice. Then my dad shows up, and our only common language - the closest common language - is Italian. My Pakistani father and I have to... I literally cannot escape this language. I know it's my colonizer's tongue, but I can't escape it. I have to know Italian to speak to my estranged father and learn about my history.

I grew up stripped from that opportunity, that history, that culture, that community. I really didn't grow up with any Desis. I grew up with mostly African-Americans, West Africans, Ethiopians, and Caribbean folks. Just honestly, everyone Black.

You wanted a lore drop.

Damon Barnes: That was a lore drop.

FS: I met Dr. Umar a year ago. I knew my black card was certified when he called me “beautiful queen”.

DB: Not Dr. Umar! Where’d you meet him?

FS: Yes, I met him at Coppin State. He was doing a seminar. I'll say I don't agree with his heteronormative or anti-LGBT remarks but that guy is funny. I'm not going to lie. That guy is funny. His takes on capitalism are rooted in heteronormativity because that's the only way he's seen the African-American nationalist movement work - the only system he studied in school was heteronormative.

Somebody needs to radicalize Dr. Umar, and it'll be me. I'll radicalize him. Wait till he finds out about queer theory. I studied Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies in college.

DB: Hell yeah. How was that?

FS: It was cool. I didn't like most of my classmates. I went to a PWI. You have to understand - there's not a drop of generational wealth in my family... we're not even doing okay in this generation, let alone wealth. There's nothing there. No one owns a house. There's not even Section 8 I can inherit.

I went to this PWI that costs like 60 fucking bands a year on scholarship, thinking shit would be cool and that I could be myself. Then I realized people don't know how DC n*ggas are. It was so interesting. I don't mean this as some mixed-race "too Black for white kids" dilemma.

But truly growing up in DC, I had privilege being lighter-skinned, ambiguous, and very pale in Black spaces. I went to all-Black schools. People assumed I would succeed - that's how colorism benefited me. Then going to white classrooms where I was seen as... I'm not even joking, a gangster. I was assumed to be aggressive. People were surprised when I was well-spoken.

I don't think people realized I just didn't code-switch, not because I couldn't, but because I didn't want to. I've always been able to articulate myself in academic theory-based modes of knowledge production. I've always been community-oriented, like my mom. Going to a PWI was insane. It really opened my eyes in the worst ways.

DB: The stereotypes surrounding smartness are really fraught.

FS: I think in every space I embody, I want to examine the norm. Understand why they're there, not fully give a fuck, and like be myself regardless of like the respectability while also carrying some sense of like self-awareness of like consideration. I don't know. Like, I could sit here and tell you about like how much I struggled being super poor. And I think I could sit here and cry about the struggle that I experience, but the missing piece is always like acknowledging what you have or not even just what you have, but just looking at the like bigger picture of like, Yeah, okay, I struggled. We've all fucking struggled, but like where have I benefited? Like how how did I play into those systems? Like how did that shape me?

Like being someone who was always chosen and picked to be favorite. I was pretty much taught at a young age that I had the skin to win. As much as I felt ostracized by my own community, right? I can go on and cry about it and be like, "Oh, I don't speak Amharic." Because no one in my community ever assumed I was Ethiopian. Okay, boohoo. You know, it sucks. It does suck. But like also like, you know, I lost homeboys along the way. I lost someone who was a childhood crush and knew him up until we were both like 18. I lost him to gun violence. He was on my grad cap for GED school, you know. I think there's just bigger things [in life], and we have to look around and realize what played in our favor and how people get to where they are. I think that's how you really have true empathy. Not even just social skills, but like the real key to understanding people and the key to understanding how you want to live.

DB: Well said. I know you just settled in your new residence in Baltimore. How does it feel to call Baltimore home now?

FS: I think DC is always my home. I'm sorry. Like Chocolate City all day, every day, baby. No tea, no shade. I love Baltimore, but D.C. is really my home. Like, D.C. is so my home that my Baltimore homegirls all make fun of the way I talk. I have Baltimore girls coming to me talking about "oh what, purrrr" "on my muva, on muvas" like they know...

Damon Barnes: They know.

FS: D.C. is so within me, and I'm just so grateful my mom let me experience the city and the real culture behind it, and let me experience all these things, and didn't stigmatize them. Because I think there would be no ‘Baltimore being my home’ had I not had the real DC experience. You know what I mean? People in Baltimore are so fucking friendly. It reminds me of Northeast growing up because everybody says hello on the street. Yeah, I feel good out here. I love Baltimore. I hope to one day have a house on the outskirts of DC and then also a house in Baltimore. I love that MARC train.

Damon Barnes: The train. Yes...

FS: I love the train purr.

DB: You were present in the scene before the pandemic, before I got active. I don't know how the scene was pre-pandemic. How does the music scene now compare to before?

FS: Um... well, I want to start with a moment of silence for RIP... was it Milkboy in College Park? I think also Velvet Lounge in D.C. RIP to both those places because those were definitely places people used to book shows with.

It used to be like... you could just rent out a space and throw a little show and make a little money, and get a little fan base. It was so goated. Pre-pandemic the algorithms were different - I used to post that shit and everybody and their mother would show up. I felt like a marketing genius at 17, 18, 19 throwing fucking shows where hella people would show up.

Now it's hard for artists to pull crowds these days. I be having to get people hip to how to market. You can't just post shit nonchalant anymore. That's why for Out the Wrapper, I did the whole three-skit layout - multiple meetings planning with Steve from 10 Fold Collective and Maiya. We had to make multiple advertisements... one was "Where's the tape?" - a whole skit with everyone looking for [the tape], then "Oh, we found Sokka's mixtape." Then the Cupid skit... whole thing requiring color grade, edit, shoot days.

It's way more work now. Music just... it's oversaturated. You have to stand out so much more. Standing out is so hard. Sometimes I wish I didn't take a break, but who knows if I'd be alive if I didn't? Capitalism makes you feel like you wasted time when really, you were just living.