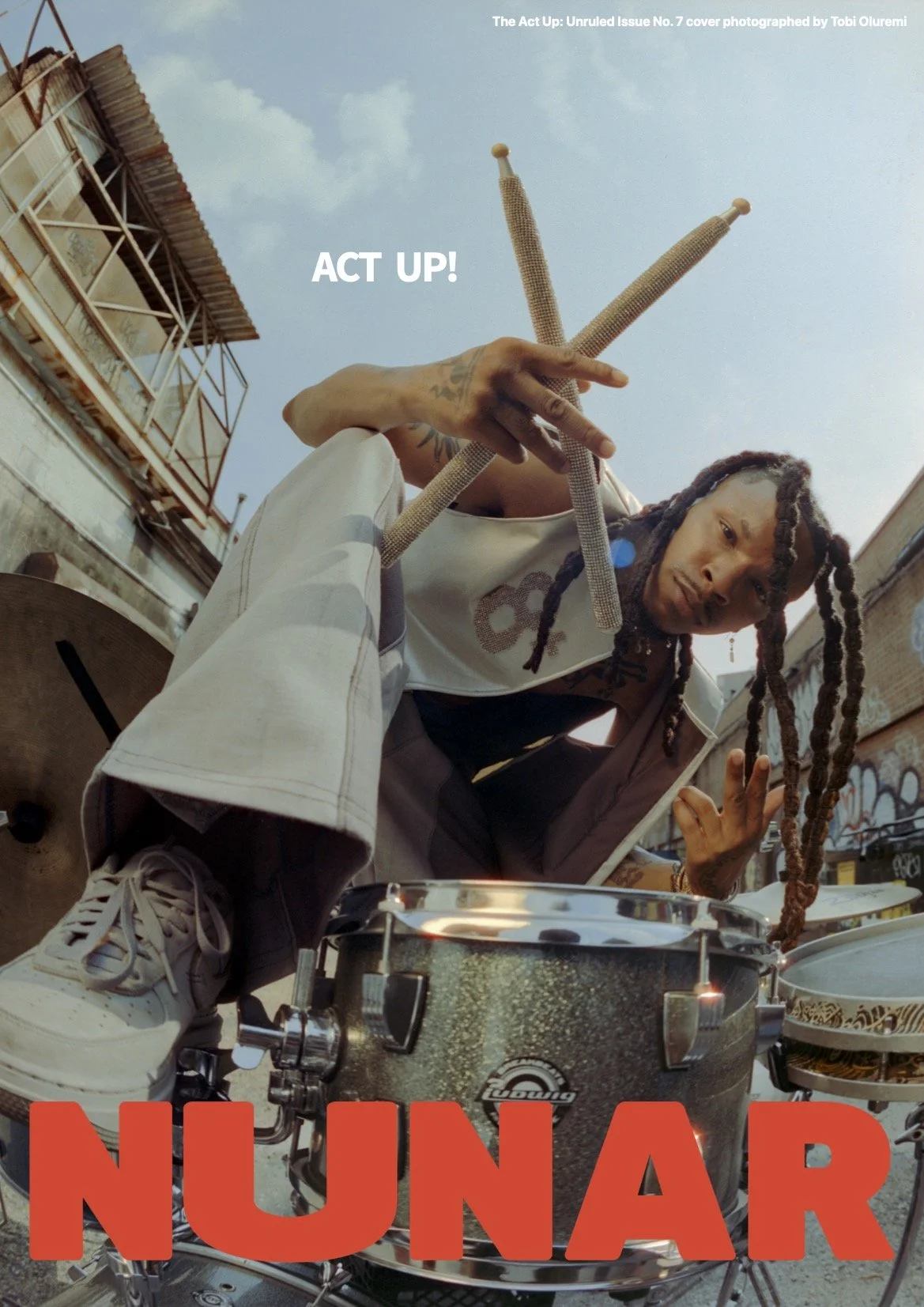

Malik DOPE is Carrying Go-Go Into a New Era

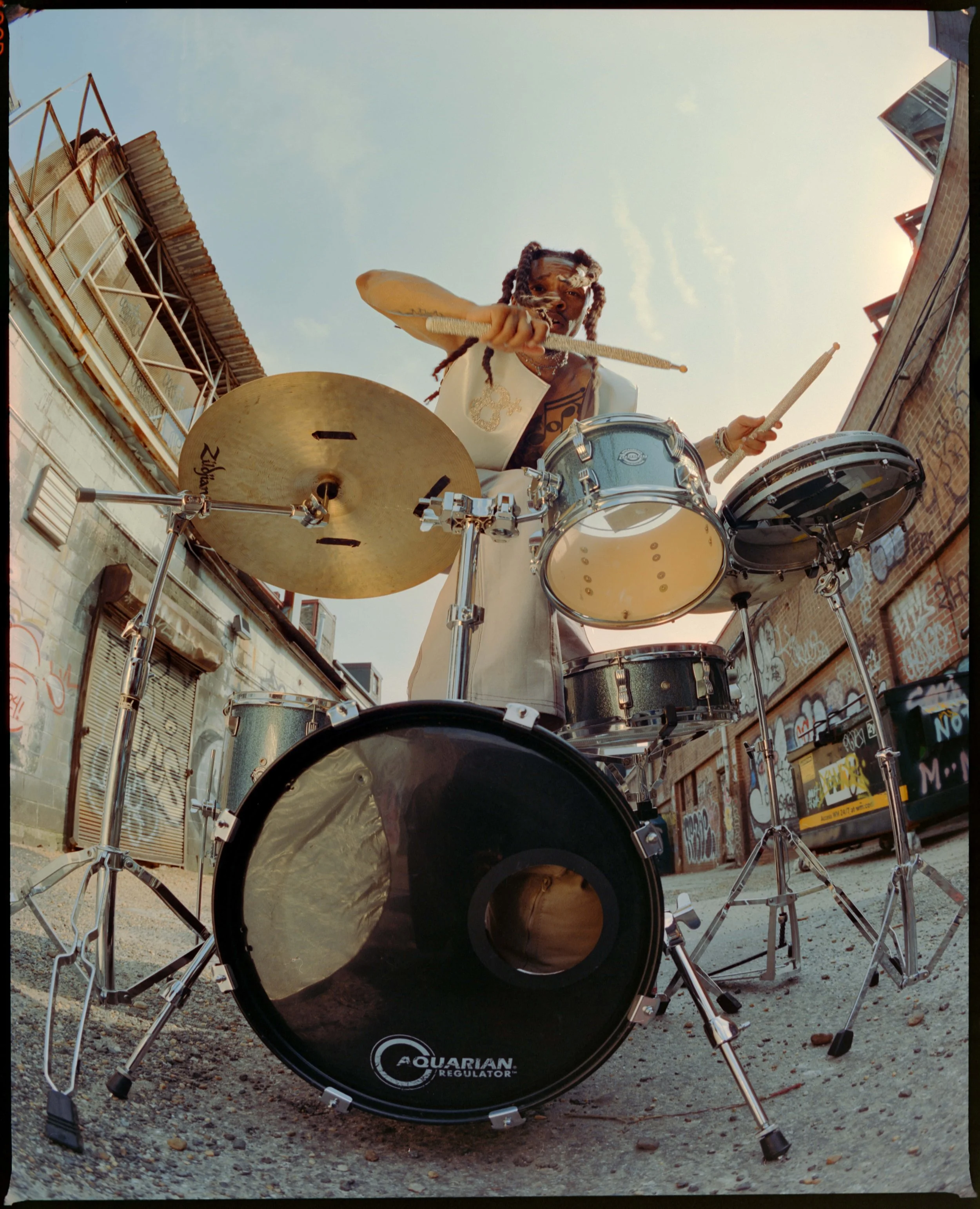

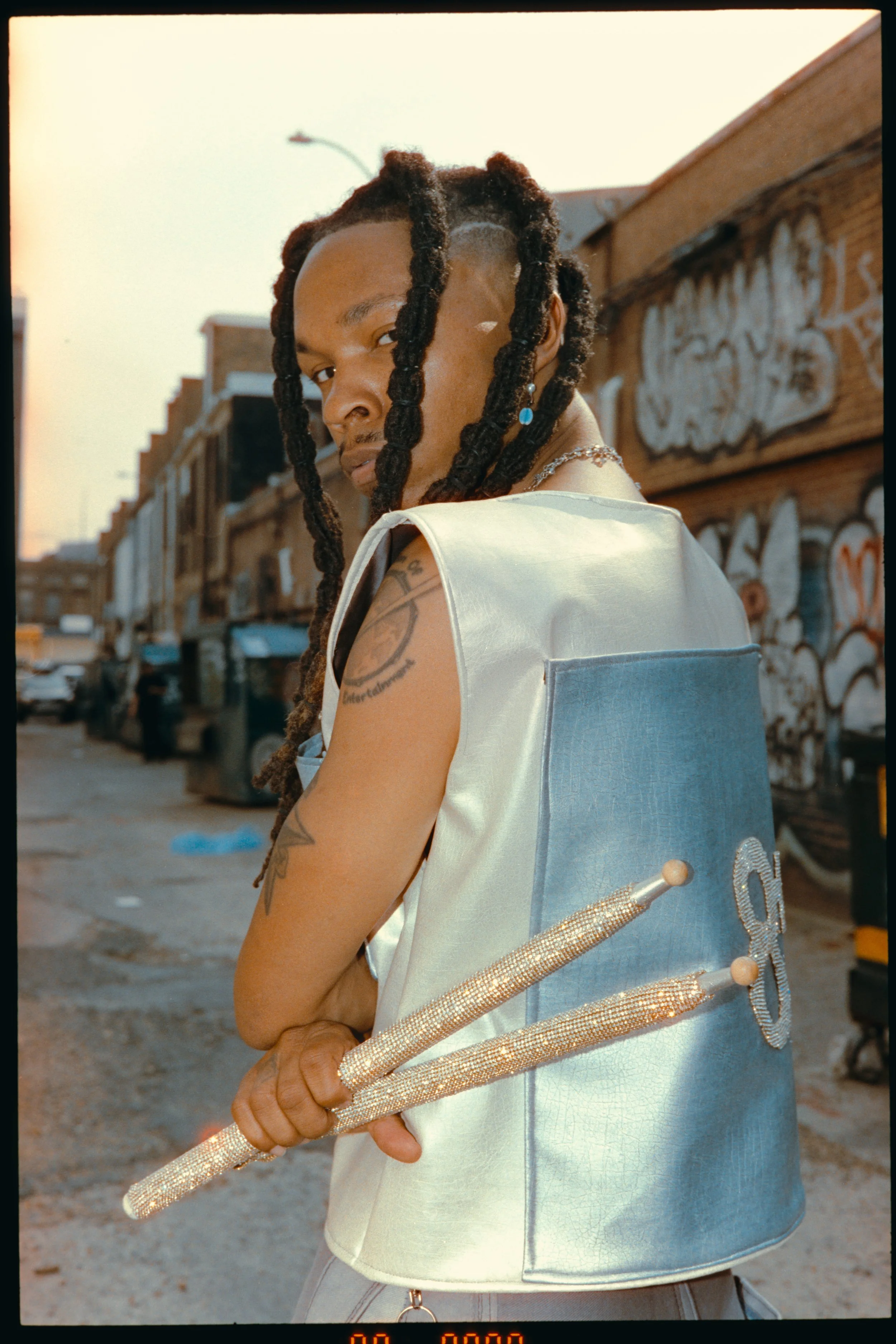

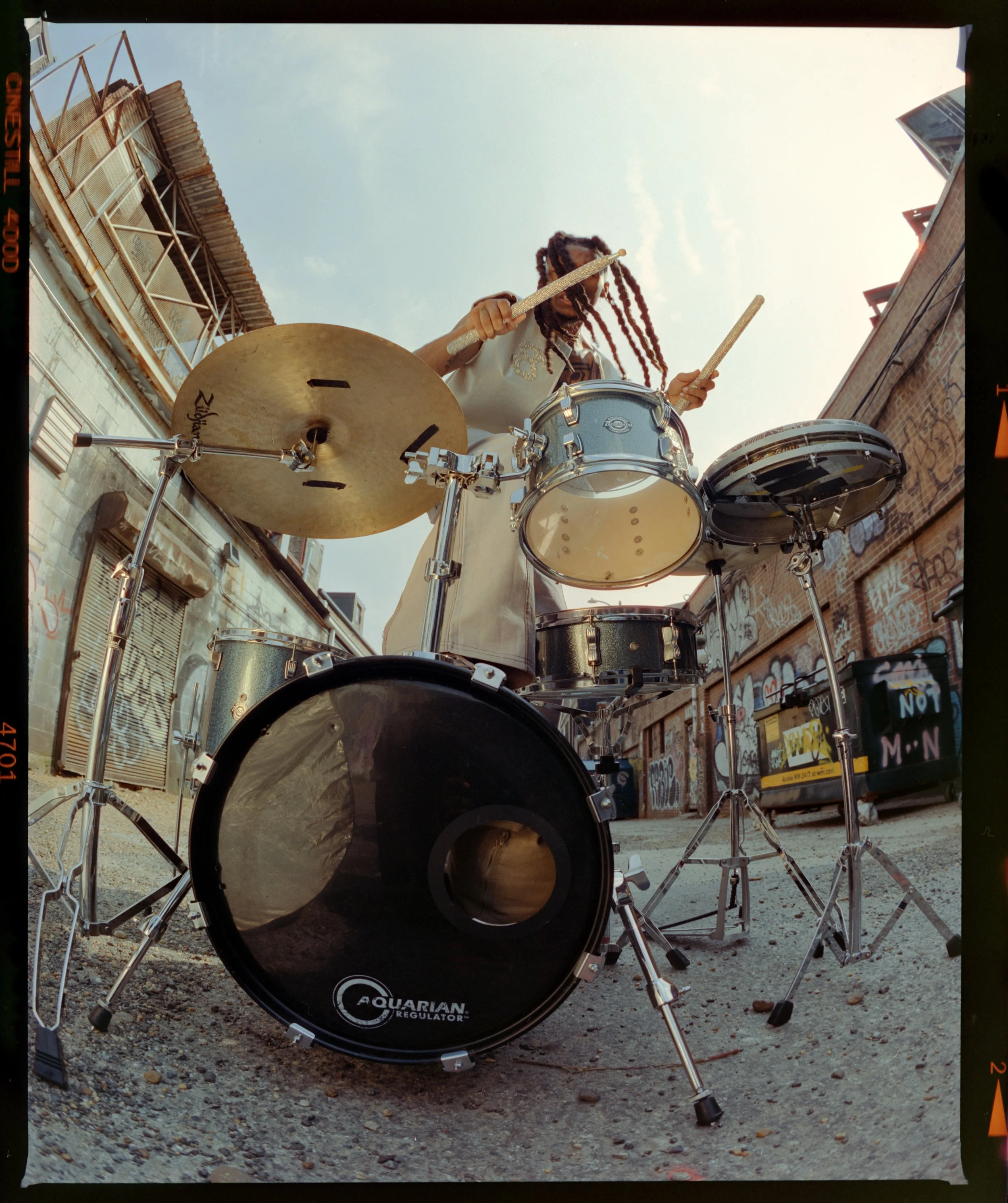

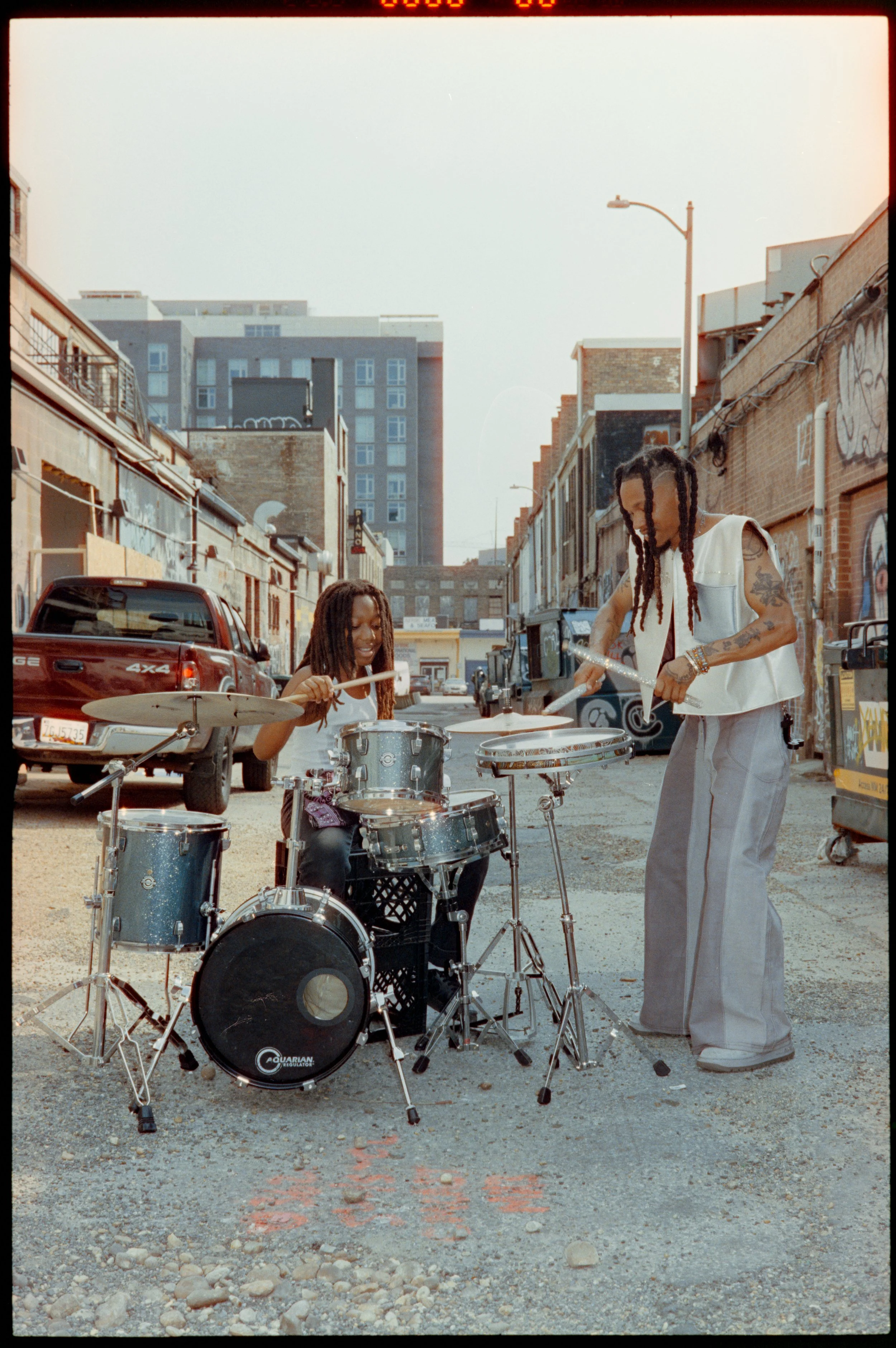

photo by TOBI OLUREMI; fashion by EYEWUH, MORIAH TSHIHAMBA; lighting technician ERIC JOVEL; key PA CHARLES SYKES

In 2020, the world met Malik DOPE when he owned the stage of America’s Got Talent, fusing an energetic performance of his “Wae-work” drum and dance style to Busta Rhymes’ verse on “Look at Me Now” and J.Balvin's "Mi Gente”. In front of celebrity judges and millions of viewers, Malik would advance all the way to the AGT semi-finals before being eliminated. But by that point, he became a global sensation and a hometown hero.

Between takes for his NUNAR cover shoot in the back alley of SOMEWHERE DC and on the corner of Gallery Place-Chinatown where he first cut his teeth, the AGT alum keeps getting interrupted by fans and people in the community. Spontaneous meet and greets with young children. Old heads calling out, "I love this dude!” Passerby fist bumps and hugs. Malik resides in a city that knows and loves him.

Born Malik Stewart in DC’s uptown neighborhood LeDroit Park, he didn’t just grow up around the rhythm of the city – he was forged by it. His parents’ participation in local African drum and dance circles as well as DC go-go and arts initiatives in the area was a musical entry point – and Backyard Band’s "Fakin' Like" offered his first connection to the spirit of go-go music. He joined his first go-go band at age 12 with childhood friends, which cemented Malik’s interest in drumming. From 12 to 19 years old, Malik began to grow as a known performer in his neighborhood for his participation with various Go Go bands. Inspired by street performers on Canal Street on a trip in New Orleans, Malik started street performing under the DOPE (Definition of Percussion Entertainment) brand at age 19, quickly finding success across the country. “I made $200 in like two hours at 19 years old, just drumming. No speaker, just sticks and a drum… from there, it just clicked.” This experience led him to quit his job at Home Depot in 2013 – never work a 9-5 again – and become a full-time street performer, incorporating drumming, music from a speaker, and dance, including homestyle beating his feet, into his acts.

Beyond AGT, Malik DOPE has graced iconic stages worldwide—from TEDx and NBA halftimes to the Smithsonian and G20 Summit in Brazil and more. He won a televised talent show in Amsterdam, filmed his "ELEVATED" music video at the Egyptian pyramids, and has brought his street performances everywhere from Tokyo to Venice Beach.

A culmination of his core influences Bob Marley, Bruce Lee, and Michael Jackson, Malik DOPE has carved his lane as a performer and is spreading his ambitions. Now a father of two, Malik is setting his sights on inspiring a new generation of gogo percussionists. This year, he announced the launch of the United Nations of Go-Go Music, a cultural diplomacy project to train gogo bands and seed the genre across the world. “I'm currently working on starting a GoGo band in Japan – that's closest to launch – and developing projects in Brazil and Cuba.”

The ingenuity of Malik DOPE lives in this duality: a global stage artist and advocate for a genre in need of preservation. A pioneer in many ways, he is also the inventor of “8+ Stick It”, a fashionable mobile drumstick holder. This follows up his signature marching drumstick, the “CHOPx1,” made with one of the world's top drumstick manufacturers, Vic Firth, making Malik the first percussionist in the DMV to have his own marching drumstick. Whether he’s inventing the 8+ Stick It for drummers worldwide, planting go-go bands across continents with his United Nations of Go-Go Music initiative, or dropping his upcoming hip-hop album TUFF, one truth remains – this is still the same genuine neighbor of many who watched him turn street corners into a sublime stage long before the world knew his name.

I talked with Malik about his early influences, transition into fame, fatherhood, and why it’s time for go-go to take root around the globe. Here’s some of that conversation:

Damon Barnes: I learned that you started drumming at the age of five. Was there anyone in your life encouraging you to value that artistry?

Malik DOPE: The encouragement – I will have to give it to my parents – starting out because my mom and dad, they were heavy in the DC go-go community, the African drum and dance community, through the cultures of Rastafarian practice. My dad hung out with some of the go-go legends from Rare Essence, like Little Benny & the Masters, and, yeah, just grew up in the whole Southeast DC upbringing of the start of go-go. My mom being more on the uptown side of LeDroit Park, had her first job with Mayor Marion Barry’s summer youth program, which would foster things like kids getting paid to be a part of dance and just all types of artistic collectives.

So that really fed the community by literally providing funds to the community as well. So through that, they would put me in different stuff like Kankouran, African drum and dance which just fed my brain a lot of artistic influence.

DB: I love that. So it was in the family, and it was easy to sort of be immersed in the musicality, especially rooted in DC.

MD: Yeah.

DB: What were your first experiences performing for an audience like? When did you realize you could entertain a crowd?

MD: Man, that's a good question because – let’s see, man, you making me go back now. So, of course, I went to schools like Roots [Public Charter Schools] and Kuumba. I think that was for kindergarten and pre-K times. So we would probably have showcases for parents and stuff like that – there's stuff I can't remember so much but I know then I was active for sure.

To fast-forward to stuff I can remember – maybe when I was about six or seven, my family also put me in Kung Fu. They put me in the Dennis Brown Shaolin Wu Shu Academy, which is located in Silver Spring, a little close to Wheaton.

And I remember we would do exhibitions during that time. One exhibition we did was performing at Six Flags near the wave pool on a stage. We demonstrated martial arts for the crowds watching. That was an early performance time. I was probably seven or eight—something like that. And yeah, doing flying kicks and stuff, I'm just like, "Oh, this is a little different with shoes on, a little heavier." But yeah, it was fun.

I always participated in school things. So, in elementary school, I went to Thomas Stone Elementary, which is in Mount Rainier, Maryland. And they had something called Colors, led by a guy named Mr. Cook. It was almost like a Broadway music production—dance ensemble, jazz, all-encompassing program. And I was a dancer there. We had showcases at the school, and at would later be my high school, Northwestern High School, which is in PG County, right there by PG Mall.

So we showcased that, where I was doing various styles of Latin dance, hip-hop, and Broadway musical-type singing stuff and more. So all of these experiences – from the martial arts side, which now you see in my crazy drum-and-dance stunt-like work – to being in these other dance programs or African drum and dance stuff—it kind of just really formed who I am now in how I express my performances as people see today.

DB: Wow, that's incredible. Kung Fu—I totally connected that. You be jumping, you've got quick reflexes.

MD: You know, my three main guys that I want to be like or exhibit in my expression are Bruce Lee, Bob Marley, and Michael Jackson.

DB: Oh, wow.

MD: Bruce Lee, Bob Marley, Michael Jackson. Those are the three guys. I used to be in this Bob Marley trance because I remember one time as a kid, we went to Jamaica, and I went to Bob Marley’s house—like, you know, how you can visit a memorial site. And I went under the things, and I was jumping on his bed. Wasn’t supposed to do that. But I think I got embedded, or whatever, with the spirit of Bob Marley, because then I would spend hours in front of the TV acting like I was him, reciting his lyrics.

I would put a towel on my head because I had shorter Rasta locs. I would put a towel on my head to represent his long locs, and I would have a broom or a mop or something to represent a microphone, and I’d be acting like I’m him for hours, like in a trance. And with Bruce Lee, you know, I would watch his videos, especially when I was in Kung Fu. I was skinny like him, same kind of build. I’m like, "Man, if he could take down these guys, my little ass could do it too."

And then, with Michael Jackson, I feel like we’ve all been influenced by Michael Jackson in some way – for his incredible production of music, his diplomatic influence, his music videos, everything ! So yeah, those are my guys that I look up to. And as far as ladies, later on, as I got more knowledge, I wanted to embody energy like Sheila E, who was the drummer for Prince.

She did her own song, "The Glamorous Life" And she would be drumming and singing her music while dancing too. So, it’s mostly, of course, because I’m a male, there's been more guy influences, but I had some women influences as well.

DB: I was just watching Krush Groove, a film about the founding of Def Jam, and Sheila E was in there with her drumsticks. I thought of you. I was like, ‘Oh, wait.’ She was performing a freestyle rap and did a trick with her sticks. So, I know go-go has been a really big part of your influence and how you started getting into more percussion performances. When did you first connect to go-go, the scene? How did you find and navigate the street performance scene?

MD: I first got connected with go-go around 11, 12 years old. Because I didn’t really like go-go at first—I was more a kid and didn’t really understand the whole ambiance of the ensemble, the whole production of it. I remember the first go-go song that I liked was "Fakin’ Like" by Backyard Band. I heard it on the radio because, you know, 95.5 and all of them would have the go-go times where they would play all of that stuff. So I got really connected with it spiritually for me at that time. And, of course, my mom would play it, and my dad would play it, but that’s when it hit me personally.

I started being in a go-go band at 12 years old because one of my friends, Tyrell Willis Holland—I always say his whole name, it’s stuck in my head—elementary school friend Tyrell Willis Holland came over because I had a drum set since I was six years old that was gifted to me by one of my family members from Virginia, but I didn’t really tap into it like that. I always messed around with it jokingly. But then I actually started playing on it after Tyrell came and annihilated it with a dope bounce beat or a breakdown beat, which is the drum pattern from “Fakin Like”.

So once he did that, I was like, Oh nah, I want to be a go-go drummer. I want to be a lit go-go drummer. You know what I’m saying? And yeah, that’s when I just started. I took my drum set from my grandparents’ house, which was around the corner from me, and then I brought it over to my house. And then I just started practicing DC Go-Go bounce beats, pocket and socket beats, and other patterns – but mostly go-go stuff because that was like the cool thing to do. Go-go was just famous, rampantly lit, you know what I’m saying?

DB: Certainly.

MD: So yeah, and then I began to be in go-go bands. The first go-go band name that I was ever in—I think it was called… I can’t remember the name. I know we were in one of my friends’ basements—my friend Markese. But then I was in another band called Black Presidents Band. That was when Obama was just elected as president the first time. So we were in Black Presidents Band, and we ended up changing the name later on to Sky High Band.

I would go on to be in the marching band at my high school, Northwestern. That gave me more skills with the rudiments and the drum patterns to be able to execute at a higher level. And then later on, I’d be in one of my most successful go-go bands—starting probably from 16 to 18, or at 19—it was called Future Legends Band. And we would go on to open up for acts like ABM Band, Reaction Band, TCB.

After that, I kind of faded off on the go-go band thing a little bit because I was getting more into graduating out of high school. I graduated high school late at 19 years old, going on 20. I’m like, I got to get out of high school ASAP. So I finally got out of high school.

And then, my friends and everybody, they were going to college and had scholarships, and I was like, Dang, I’m not going to college like them. I did end up going to Prince George’s Community College, but I didn’t get the marching band experience yet or anything like that because I was just in that little gray area, little mid-space of trying to figure out what I want to do with my life.

So next thing you know, I dropped out of P.G. Community College. I remember one day I was drumming on my little practice drum pad at the PG station bus stop because I was about to go back home, and one of my now friends and brother, Dereck Allen, saw me, and he was marching in the Howard University Showtime marching band drumline. And so then, next thing you know, he said, "Do you want to be in Howard University’s drumline?" Because they needed some members, and I had some good skills.

So I was like, "Yeah." You know what I’m saying? My mom went to Howard in the ‘80s and everything. And I grew up around there in LeDroit Park, which is right in the neighborhood of Howard. So I was just like, yeah that's a dream come true to live the HBCU experience, even though I didn’t have a scholarship or anything. I just had the merit of my skills.

Fast forward—I marched for Howard band from 2012 to 2015. Then that’s when I was more like, "Alright, it’s not enough for me, I need more. I want my talent to speak to the world. I want to connect. I want to be a star in some type of way."

So me and my mom would go to New Orleans different years—Essence Fest, Mardi Gras, stuff like that. So one year, I brought my snare drum, just a snare on the stand, and I was like—because I would see people street performing out there, "Man, I keep seeing everybody express themselves out here. It’s like a circus of just expression and art and music. I’m about to do it."

And then at 19 years old, I made $200 in like two hours, just drumming. No speaker, no nothing, just sticks and a drum. Many people would walk past me right on Canal Street, which is like the main strip in New Orleans.

And yeah, from there, it just clicked. At the time, back home, I was working at Home Depot, overnight stock position. I quit that job. I bet on myself, and that’s when I became a street performer, starting in like the years of ending 2012, really 2013. So that’s when I became a street performer.

And literally about every year, I went viral in some type of way. I would start with a drum, then I added a speaker because people liked when I played the drums to music, and then that’s how I started drumming and dancing with it too. Because the first dance move – which is a dance style in DC, "Beat your feet" – I started incorporating "Beat your feet" into my already rudimental drumming with stick tricks and stuff, marching band-type style. And that’s where I would end up defining my drum and dance style “Wae-Work”.

DB: So, you street performed in New Orleans. Are there any other cities you've ever street performed in?

MD: Oh yeah. Um, so of course I started in New Orleans, and I took it back to DC immediately. I went to New York. I went to Baltimore. I went to Philly. I went to Music City, Tennessee.

DB: Mhm.

MD: I did LA. You know, I would be at Santa Monica Pier, Venice Beach, Hollywood Boulevard. Um, and I’m sure there’s some other cities that I just can’t remember right now. But I found an energy and a vibe in every place. I was using social media because Instagram started popping off around that time—2013, 2012-ish.

So I was just using a hashtag of my first brand, Definition of Percussion Entertainment, which was—you know, the acronym was D.O.P.E. So that was my first real way of branding myself using hashtags. I would use that as a hub for my brand. People would also use the hashtag and connect with me. Remember when everybody was using a hashtag they aligned with? It really showed, like, almost a membership of dope people, dope drummers that would be along with me.

Um, and yeah, I would use that, and I would travel around a bit. At the same time, I would create posters for myself so I could get booked and stuff like that. Like, I would draw just my name, the brand name—and put my social media on there and my email.

So that would lead me to getting booked for schools, events, clubs, private events, parties, even corporate events in some ways. And yeah, I just worked my way up through collaboration and putting myself out there.

DB: That’s what’s up. Yeah. I mean, just being able to stand on the street performing and really pour your talent – your heart – into performance has to be a mental… hurdle?

MD: Yeah, what you just said right there – street performing was definitely a mental hurdle. It didn’t take long for me to cross over… I always had the confidence, but sometimes your confidence is really tested when it’s like no one’s really watching, or it’s a slow day.

Um, or like the police telling me you gotta stop because of some sound ordinance or something like that. So it forces you to be your own activist in a way, your own coach, and just practice self-resilience through wanting to express yourself to the world while facing these different hurdles or challenges coming your way.

But, you know, if you can get through that, it’s really a great investment in yourself internally and to the other people watching you grow. Because people watched me from the ground up to all of my fame or world-renowned energy now. Before I was on a TV show or anything like that, everybody really walked past me. I was a regular person – of course, we’re all gifted with different skills, unique talents – but I’m a person who really did back-to-back skill building and work ethic to get where I’m at.

And that don’t mean I did it solely by myself. It always takes healthy collaboration – and sometimes unhealthy collaboration, meaning like, Oh, I shouldn’t work with these people no more because they not treating me the best. You learn all these things when you put yourself out there.

And street performing was like one of the rawest forms of putting yourself out there—to just learn how to develop financial literacy as well. You know, I’m counting money. I wasn’t paying taxes, of course, because it was just tips.

And I was a dependent at the time, living with my parents. But you just learn so many different life skills. You even learn community energy – giving back. There’d be homeless people out there. I fed a lot of homeless people over my time with street performing. That was almost like a ritual, a part of me doing it.

I call it paying my spiritual tax.

DB: Yeah.

MD: Because I would see people digging in trash cans – you just see what people are really going through, from homelessness to corporate America. I’m seeing them get off work, go into work. I’d still be out there, and sometimes I was just the soundtrack to their life, and mostly an elevated soundtrack where they just needed to see me that day while they were on break. You know what I’m saying? I’m a person who kept people going. I kept some people from killing themselves. I fed some people to where they was just about to rob somebody just to eat, and I’m like, "Nah, man. Here, take this $20."

And people would see that because I’d do it while performing, and had a whole crowd. A part of my show was literally giving back. I would – while the music playing – take some money out of my bucket and give it to somebody I’m seeing dig in the trash can right near my show. People would see that, and it would actually make more abundance come. They’d be like, "Man, that’s amazing," and they’d triple, quadruple whatever I just gave the person.

At first, of course, I was doing it because it was the right thing, but then I saw it was a cycle—I’m doing this, people see it, they’re gonna know who I am, what type of person I am. So it could look performative, but it was actually who I was. So if I’m receiving energy back, I think it’s justified because I did this when nobody was looking.

DB: Mhm.

MD: So yeah, man—street performing. I don’t regret it.

DB: You've done TEDx, NBA halftime shows, performed for the Smithsonian, Disney, and even the G20 Summit. You've even won a nationally televised show in Amsterdam. How was it to transition from that sort of do-it-yourself setup of street performances to top-of-the-line stages around the world?

MD: Man, it really is about the self-talk that you have with yourself. Because when I was street performing, I always treated it like it was my big stage. Like every street I've been on, it was my big stage. Sometimes I would cancel out thinking that I'm just street performing. It was any of those stages you said, even though I wasn't there yet. It was that stage already. So it's all about how you envision internally where you want to be – you know, manifestation to actualization. That's a really big, important step that one has to take in the spirit. Also, your mentors, who you have in your corner, even if it's one person. I've had different people in my corner: family, friends, strangers. The world has been in my corner at different points in time because of what I also emanated out to the world.

DB: Mhm.

MD: So I think it's a factor of all those different elements combined that will feed you—feed your soul, feed your physical, feed your mental, in order for you to express on higher and higher levels. It's not a lone game. It's your tribe, and the tribe is interchangeable. But you must always have the code of This is my tribe in the moment. You know, same way how you build a team with NUNAR. You can't do it by yourself. Maybe you had a vision, but you knew that you needed elements to complete that vision.

DB: Yes. Mhm.

MD: So that's what leads to success—to build to get to these higher levels. You, the individual, are still the main key, but there are other elements that will help propel you more than you can even prepare yourself.

DB: Absolutely.

MD: And preparation meets opportunity. You still have to have the skill and the talent, you still have to have that work ethic already as the individual self. Because when the opportunity comes, whether to perform on a big stage or to have a budget or energy where people want to work with you, you must know how to lead. And in order to even be a good leader, you would have to had been a great follower of something.

DB: More into your time on AGT— what was your most surreal moment?

MD: When you're on a show like that, you're just in the performance part of it. You're not going to realize how big it is until you're looking at reposts of people watching you on their TV. When you're seeing yourself in everybody else's household, that's when you're like, "Dang." Because unless you have your own system to get to everybody's household tv, you're not going to be able to get to that. But using that platform, which was America's Got Talent, or NBC Universal, it was crazy to see me in other people's households all across the world, not just in America.

And you know, that gave me great appreciation for myself, appreciation for anyone that's helped me get to this level, and a drive that was like, Okay, I got to keep going. And a little bit of pressure, too, because you want to keep up the energy. Now, after that, no one sees me as a street performer, Malik, or whatever. They know I started like that, but they just see me as a superstar now. And there's a gift and a curse with that too, because people will separate themselves from you – they don't feel like they relate to you no more, don't feel like they have the same access to you no more. Or jealousy could kick in where they feel like, I deserve that or I want that, so they feel competitive or some negativity because they may be lacking that opportunity.

DB: Mhm.

MD: But for me, it put me into the first beginning levels of what some celebrities go through daily or what they've gone through in their time coming up, because some of them have also been through America's Got Talent or American Idol before making it to bigger levels after. So I'm like, damn, I'm on a route to that status too. Wherever my way of it will be, but I have to look out for all these different pressures: other people being predatory, just trying to get some energy from your shine, the clout chasers, opportunists. We're all opportunists in some way, but there's healthy opportunism and unhealthy opportunism. So you have to learn or already know how to differentiate these different characters that pop up out of nowhere. They might want to offer you money, offer you this, offer you that. You got to look like, "Okay, do I align with that? Do I want to be used as a political instrument for something I don't represent?" You know, it makes you question your identity, not in a way of not knowing who you are, but making sure you're not compromised in a way that doesn't serve you.

DB: Discernment seems like a big thing to learn for those of us on that path. This year, you announced that you were launching the United Nations of Go-Go Music and aim to utilize cultural diplomacy to promote go-go globally. So why is it the time now for go-go to go global?

MD: Well, yeah. I want to say that it's been global – go-go's been global – but I'm trying to re-globalize or upscale it. I'm trying to globalize it more because, for the generation I come from now, we're 30 years old. I'm 33 this year. And I look at the youth… there are not so many youth starting go-go bands like how it was when I was coming up. So by the time I'm 50 or 60, they won't be in their prime to keep it going.

I'm seeing that there needs to be a resurgence of effort into making it go further, not gatekeeping it, but appropriately managing and dispersing it worldwide. Because right now it's sort of dying out in DC. It's only being upheld by some founders or earlier go-go bands from the 80s/90s,2000s. It's not really growing from that era.

DB: So, younger groups aren't coming up as much...

MD.: Yeah, not as many younger groups like when it was my generation or your generation. So now I'm shifting to address this. I saw a problem and solution where go-go bands would go overseas, but weren't planting seeds by starting local go-go bands in those countries. There are bands in some places like Amsterdam or Rotterdam playing more old-school socket pocket styles that blend with jazz, but I'm drawn to bounce beat energy as well – it sounds tribal, like African drum or Afro-Latin percussive patterns.

My definite goal is to start go-go bands globally using existing knowledge. This would strengthen cultural diplomacy and elevate go-go’s socioeconomic status worldwide. These international bands could then open for OG DC bands like Backyard Band or TCB, creating celebrity status for bands abroad. It could spark virtual collaborations or funded exchanges to bring international bands to DC. I haven't seen this level of cultural alliance yet, have you?

DB: No.

MD: Yeah. So I'm currently working on starting a go-go band in Japan – that's closest to launch – and developing projects in Brazil and Cuba. Another piece is creating a book that transcribes go-go percussive patterns into musical notation for schools worldwide. The book will include those polyrhythmic patterns in standard notation along with tutorial videos using clear, translatable language. You can create a concerto piece on go-go because now you’ll know how to read the rhythm. This rubric will standardize go-go education internationally, whether through sheet music or subtitled videos, to unite the understanding at the highest level.

DB: That’s incredibly inspiring. You became a father to your daughter in 2021. How do you continue to honor your career and navigate being a public figure while settling into fatherhood?

MD: Great question. Um, I'm still navigating that as she grows older. There are certain needs that have to be met. Maintaining communication with my daughter's mom—we're not together—but it is still important. I'm in a different relationship now where I also have a stepdaughter who's 10. So it's about maintaining communication and working hard to handle the finances and other growth elements that come with the journey.

But finances aren't the only thing. It's also understanding what the mom's going through on her side and what I need to do. It's a group effort in that way. Just respecting that as much as possible through the challenges and making sure I'm being present as much as I can. That's a sacrifice you take as an artist—you might be on tour and miss a birthday. Like in 2023, I missed my daughter's birthday because I was on tour. I spent time with her before that, but missing the actual birthday day... that could make you feel a little sad, which I did. Even though I'm seeing the world and all that, my best creation is my child. Nothing would ever top that.

That's the highest creation you can give to this world – a child, in my opinion. But yeah, I love her. Shout out to my daughter Coba and my stepdaughter Zara. The stepdaughter side is more new, but Coba—that's been something I'm always adapting to as she’s younger. She's three and the other one's 10, so just different, you know. Adapting with it, paying attention to what's going on in the world so I know how to educate them on various topics. I'm built for it—I don't feel like I'm not, even if I'm struggling in the moment. Things are just momentarily happening. So yeah, I'm with it.

DB: Does Coba know who you are at this point? Like, oh, daddy's a world-renowned percussionist.

MD: Yeah, yeah. There's something very spiritual and amazing about not only being a dad but being her dad while also being this celebrity or influencer to the world. She's been able to see me on video, on different things. She calls me "yo-yo", she doesn't say "da-da." My nickname is yo-yo because on FaceTime I’d be like "yo yo yo," and she started saying "yo-yo" I like that better than "dada"—we've heard that already.

When she sees me, she's like, "Yo-yo’s drumming!" or "I see Yo-yo!" It's so beautiful to see the glow in her eyes when she's looking at me on TV and realizes, "Whoa." She knows I'm her dad, but she's like, "Yo-yo's drumming!" It makes her love for me and her memory of me stronger—she's not going to forget me because of the impression I've made as this figure to the world. I'm very thankful for that.

I love that she's even creating with me now. She's going to be on my album—she's on two tracks already. She's my number one fan of my music. She always wants to see my music videos, like my "CHOPx1" song, my "2 Charged" song and more. I don't even care about streams—I just care if she's rocking out to it. We always jam out. That's the important thing about being her parent. It's perfect getting to be this influence for her. She's not thinking about money or anything—she just knows, "That's my dad, he does cool stuff." That's just a beautiful thing.

DB: Yeah. Invaluable.